Following on from my post yesterday about the poverty and wealth in Kabul, I noticed that that the G2 section of today’s Guardian carries a long article by Natasha Walter concerning this situation of women in Afghanistan. While it may not say an awful lot that most of us don’t already know - that the lot of women in Afghanistan has improved very little overall - it is still well worth reading. It makes me shudder to think that the few gains women have made are being eroded as if made of sand.

Here is an extract from the article. Click here to read it in full.

Five years ago, when the US and the British arrived in Afghanistan, they sold their mission to us not simply as a way of driving out the terrorist-shielding Taliban, but also as a way of empowering women. As Cherie Blair said in November 2001: "We need to help Afghan women free their spirit and give them their voice back, so they can create the better Afghanistan we all want to see." Five years on, however, the Blairs have become less vocal about the women whom we were meant to have liberated. When Tony Blair visited Kabul earlier this month, he did not comment on the recent report by one charity, Womankind Worldwide, which stated: "It cannot be said that the status of Afghan women has changed significantly in the last five years."

I went to Afghanistan soon after the Taliban had been ousted from Kabul, and found that their departure was genuinely allowing women to hope again. One of the places that stuck most clearly in my mind was a dirt-poor village called Sar Asia, on the outskirts of Kabul. There I met women who had been unable to leave their houses for education during the Taliban regime, who had just set up a literacy course with the help of Rawa, the Revolutionary Association of Women of Afghanistan. When I asked the students, who ranged from 13-year-old girls to 50-year-old widows, if they thought all women in Afghanistan wanted more freedom and equality, my translator struggled to keep up with the clamour: "Of course we do," said one widow furiously. "Even women who are not allowed to come to this class want that. But our husbands and brothers and fathers don't want it. The mullahs keep saying freedom is not good for us."

Last month I was able to revisit the country, and one of the first things I did was to go back to Sar Asia. The teacher invited me back into the room that once had been crowded with women learning to read. This time, the room is empty, its net curtains closed against the bright sun. "We're not teaching here any more," the teacher tells me sadly, sitting alone on the cushions on the floor. "They were threatening us, telling us not to do it any more, and we were scared. For a while we continued, but we were afraid that they might do something worse. This place is a place of Taliban. Neighbours may work for the government in the morning but at night they are the same Taliban with the same thoughts." I tell her I remember the enthusiasm of the women in the course four years ago. "Yes, we were very happy. Rawa members came and talked about how they could help us to make a literacy course for women. We were all very pleased. But that has stopped now. I think in the west you think that now conditions are good here, that everyone can go to school or go to work for the government. But now we are just watching things get worse."

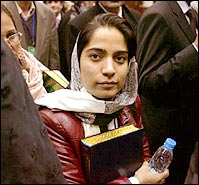

You can't say that things haven't improved at all in Afghanistan since the Taliban were "removed", You can now see women moving around Kabul in a way they could not five years ago; the majority do not wear the burka, sporting instead a variety of Islamic dress from shalwar kameez to a short coat with a bright headscarf, as they go to the markets, to the schools, to the university, and to work. During my time in the city I seek out evidence of change, and I certainly find it. I meet women in the government, including in the ministry of public health, where they are trying to deliver a package of basic healthcare for women. I meet women in non-governmental organisations working on literacy and advocacy projects, women professors and students in the university, and women in the media, including newspaper reporters and television presenters. But each of them has a negative to set beside the positive.

Malalai Joya is, at 28 years old, the youngest and most famous of all the women in the Afghan parliament. In a way her very presence in the parliament is a powerful symbol of change; a woman who had to work in secret in underground schools in Herat during the Taliban time is now able to speak out against her enemies in the parliament. She rose to fame at the end of 2003, when she made a speech attacking the warlords who still hold the balance of power in Afghanistan. On that occasion, one of the men she was attacking, Abdul Rasul Sayyaf, rose and told her that her speech was a crime, announced that "Jihad is the basis of this nation" and asked for her microphone to be disconnected. The then speaker of the house, Sibghatullah Mojaddedi, a former mujahideen leader, called her an infidel, and said that if she did not apologise she could not attend the next session of parliament.

"Here there is no democracy, no security, no women's rights," she says. "When I speak in parliament they threaten me. In May they beat me by throwing bottles of water at me and they shouted, 'Take her and rape her.' These men who are in power, never have they apologised for their crimes that they committed in the wars, and now, with the support of the US, they continue with their crimes in a different way. That is why there is no fundamental change in the situation of women."

She is desperate for people to take account of the silent women whose voices we never hear. "Afghan women are killing themselves now," she says, "there is no liberation for them." This is not just rhetoric: the Afghan Human Rights Commission recently began to document the numbers of Afghan women who are burning themselves to death because they cannot escape abuse in their families.

I meet Kochai, a serious woman more soberly dressed than the others in a long olive skirt and jacket. She has come to Kabul for the wedding from Kandahar, where she works as a police woman in the airport. She was married into a traditional family, and was abused for years by her husband. It was when her daughter then got married to a relation of her husband's, and started being beaten too, that she decided she had to get herself and her daughter away from these violent men. "I had to defend myself and my daughter," she said. The women now live without their husbands, although her daughter has not been able to get a divorce from her husband. "It is very, very difficult. I am sick of being frightened. During the nights especially I am frightened."

Like all the other women I meet on my trip, Kochai is very sure that despite all the insecurity and lack of progress, life would be far worse if western forces pulled out. "If the British and American soldiers left now, we wouldn't be able to leave our houses. We would lose all that we have."

Yet everyone knows that the Taliban are regrouping in and around Kandahar; Safia Ama Jan (see my earlier post about Safia A death in Kandahar ), the head of the department of women's affairs, was assassinated there recently, and Kochai says the actual number of kidnappings and assassinations is far higher than we hear about. "In one week six women were killed. They were ordinary women, working women, but the Taliban say they are spies of the government. They tell them, 'Don't work,' and if they do not listen, then they are kidnapped and killed far from the city." She has two bodyguards who take her to work and back, but after work she has no bodyguards - so in a way they only make her more of a target. "I wear the burka, and I change the colour of it regularly so that I hope nobody knows it is me under it. The morale of women in Kandahar is getting worse every day," she says.

Afghanistan women

No comments:

Post a Comment